Islam was tied up with ethnicity in the Philippines so studies like Isidro and Saber 1968 and Orosa 1931 present religion as an aspect of tribal life rather than as the main focus of study. Gowing 1964 is one of the first attempts at bringing together in one volume the dispersed information on Islam and Muslims in the Philippines. Since Islam was linked with ethnicity, information on Islam and Muslims comes from a variety of sources that either focuses on specific tribes or general surveys of tribes in the Philippines. There are very few general works on Islam in the Philippines, and there is an obvious lack of more recent work that presents an overview of Islam in the country.

Aside from the earlier differences based on ethnicity, the Philippine ummah is now a more diverse community that includes Sunnis, Shias, Jami at Tablighis, and Ahmadiyyas, and a distinction between “born Muslims” and converts is maintained. However, there are now Muslim communities in every province, mosques have become part of the landscape in Christian areas, Islamic schools have been established in several regions, and the number of converts to Islam is rising. Today, Islam is still a minority religion in a country where the population is 85 percent Catholic. Many Christian Filipinos have converted to Islam while in Saudi Arabia and on return to the Philippines have kept the new religion.

In the 1970s the Philippine government launched a labor migration program sending Filipino workers to the Middle East, especially to Saudi Arabia. These, in effect, helped provide a climate conducive to Islamic resurgence. The government, in an effort to end the war, launched various programs to help Muslims and promoted the idea that Islam is part of the national heritage. Other groups like the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) and the Abu Sayyaf (ASG) also engaged in armed conflict in pursuit of the creation of an independent Islamic state. The final peace agreement between the MNLF and the government in 1996 has not ended the conflict. Islam was previously identified with ethnic tribes in southern provinces but the war in the mid-1970s between the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) and government forces drove many Muslims to seek refuge in other parts of the country. These issues provided the impetus for Muslim-led rebellions from 1969 onward. In addition, government neglect and marginalization of the Muslim South resulted in economic disparities between Muslim and Christian areas. This “othering” which was based on religion, persisted in the post-independence period and affected Muslim–Christian relations. When the United States took over the Philippines from Spain, it did not impose a religion but maintained Spanish emphasis on religion as identity markers and created the Bureau of Non-Christian Tribes for Muslims and indigenous non-Christian tribes. The Spanish used the term Moro (Moors) in a derogatory way but in recent times, the word has been imbued with positive meanings by Philippine Muslims to convey courage, bravery, and self-determination.

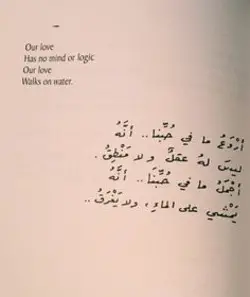

#NIZAR QABBANI SULTAN PLUS#

These, plus Spain’s negative portrayals of Islam and Muslims influenced negative perceptions of each other among Muslims and Christians. The three centuries of Spanish rule was beset by intermittent warfare in the South that combined political, economic, and spiritual motives. Spain, which colonized the Philippines in the 16th century, was not successful in subduing the Muslims or in converting them to Christianity. Overtime, Islam became a dominant religion and, in the southern Philippines the Sultan of Sulu carried the title “The Shadow of God on Earth.” Sultans also claimed to implement Islamic law and retained the services of Middle Eastern Muslims as qadis (judges).

Arab and Gujarati traders and missionaries introduced Islam to the Philippines in the 14th century.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)